Democracy, Media, and the State: A Conversation on Diplomacy with Senator (R) Javed Jabbar

November 18, 2025

We are pleased to share our conversation with Javed Jabbar, a distinguished public thinker and former Senator whose work spans governance, media reform, regional diplomacy, and documentary filmmaking. A long-time advocate for press freedom, transparency, and pluralism, he has played a pivotal role in shaping public policy and fostering dialogue across South Asia. He is also an accomplished author and filmmaker, with decades of contributions to Pakistan’s cultural and civic landscape.

Democracy, Media, and the State: A Conversation on Diplomacy with Senator (R) Javed Jabbar

Interviewer: Zahra Hussain

Senator (R) Javed Jabbar is a distinguished Pakistani writer, filmmaker, and former politician. He directed over 300 television commercials and made documentaries for Pakistan Television, including the acclaimed Moenjodaro: The City That Must Not Die. In 1976, he made Pakistan’s first English-language feature film, Beyond the Last Mountain. First elected in 1985, he is a retired Senator and held ministerial roles in three federal cabinets, including Information & Broadcasting, Science & Technology, and Petroleum & Natural Resources. He was instrumental in drafting landmark media reforms, notably the PEMRA law that enabled private TV and radio in Pakistan, and the Freedom of Information Ordinance. He is the chairperson and CEO of the production company JJ Media (Pvt.) Ltd. Beyond media and politics, he has written dozens of books, worked on environmental causes (including serving as a global vice-president of IUCN), and engaged in independent policy and voluntary work.

Q1. Could you speak a little bit about when you became interested in governance for the first time and how you found yourself on the path to running for Senator?

My interest in governance and the public sphere began as a result of my voluntary work, which I began sometime in the late 1970s. I am a filmmaker, and particularly when I started making documentaries and going into urban slums and going into remote parts of the country to create documentary films, I began to truly absorb the reality of the totality of Pakistan. I was very familiar with the urban and the middle or the upper-middle income groups, but coming face-to-face with the poor and the vast majority of the country, at that time being semi-literate or illiterate, made me conscious of the need to go into the sphere of public engagement where hopefully I could influence public policy and contribute, in two respects. One: to reform policy or introduce new ideas to public policy. Second: to be able to monitor, with some degree of authority as a public representative, the efficacy and efficiency with which policies were being implemented. So those were the twin driving factors that brought me into politics.

Q2. What was this first experience like, running for political office and then taking that role? What was your first term like?

It was very informative and educational for me. I want to acknowledge the role played by my dear wife Shabnam, who alone had the conviction that I should seek election to the Senate of Pakistan in March 1985, without any background in politics. My father was not in politics, and normally in Pakistan, politics is a process you inherit from your father or your uncle.

This was an opportunity afforded by the amendments made to the Constitution, by General Zia-ul-Haq, whom I otherwise opposed. He had introduced reserved seats in the Senate for technocrats, people who were not conventional politicians but who had expertise in a field which was thought to be valuable to the public process.

I sought election in a non-party-based poll, but even on a reserved seat one had to be elected by the provincial assembly. So, I had to go out and meet members of the Provincial Assembly of Sindh for the first time. Although some of them were already aligned with political parties, I was able to persuade MPAs, some of whom I had never met before, to cast their vote. And lo and behold, I was elected with more votes than the minimum required.

Q3. You’ve spoken about becoming a senator during the time of Zia-ul-Haq. What level of influence and freedom did you feel you had then, and how does that compare with the current political space?

I remember in the first few weeks of the Senate, I was inching my way forward. It was a very interesting and distinguished array of people, including Ghulam Ishaq Khan, Sartaj Aziz, Dr. Mehboob ul-Haq and Professor Ghafoor Ahmed of the Jamaat-e-Islami.

“I felt that one could make a difference – not earth-shaking, but meaningful – by being there and speaking out.”

As I acquired confidence and the capacity to speak, I began to freely express myself on a range of issues. I was one of the people to call for the repeal of the Press and Publications Ordinance, I supported the Freedom of Information Bill moved by Professor Khurshid Ahmed and moved an adjournment motion on the supply of outdated medication in Jinnah Hospital, Karachi. I also had the privilege of moving for the introduction of reserved seats for women in the Senate. It was opposed by many senators, but some years later, I was in General Musharraf’s cabinet when we introduced that provision and made reserved seats for women 17% of the total membership of the Senate. I felt that one could make a difference, not earth-shaking, but meaningful, by being there and speaking out.

Q4. There is a perception that Pakistan is surrounded by hostile neighbours: India, Afghanistan, and some would include Iran. Do you feel that this is overblown, or do you think this is a genuine existential danger for us?

I don’t think it’s overblown. It is a fact that Pakistan’s relations with India have been very troubled from the very beginning and in the last twelve years of the BJP, our relationship has worsened. The onus lies on India, as it has always had difficulty accepting the validity, the legitimacy, and the will of the people of Pakistan to remain an independent, sovereign country that will not accept the hegemony of India. If the government changes, it will improve, hopefully, but it will always be a troubled relationship which has to be managed in a way that is not destructive or violent.

With Afghanistan, the attitude the Taliban has taken recently toward Pakistan is very unfortunate and they are unwilling to enforce the simple principle that a sovereign country won’t allow its soil to be used for attacks on another country. We have a unique situation that requires careful management, because of the ethnic affinity of Pashtuns who live on both sides of the border. There are points where the Durand Line virtually runs through villages, and it remains a source of controversy.

With Iran, the relationship has never deteriorated to this extent. There will be phases where, because of the shared border and the infiltration of extremists from each side to the other, the situation will require careful vigilance. At the moment we also have a strange economic arrangement with them. Apart from getting electric power for Gwadar and Jiwani, there is a quasi-smuggling, quasi-official exchange of oil or goods from Iran in exchange for whatever we can export to them.

So, with these three countries, yes, we are not in an ideal situation. But it goes back to the genesis of new nation-states as a result of the withdrawal of colonial occupation in the ‘40s. You will find border troubles and tensions elsewhere too, such as Cambodia, Thailand, Africa.

Q5. Do you think the conflicts with India could descend into a full-blown war, or will it continue being the usual cycle of tension and dissipation?

There are two reasons why India will choose not to conduct a full-scale war against Pakistan.

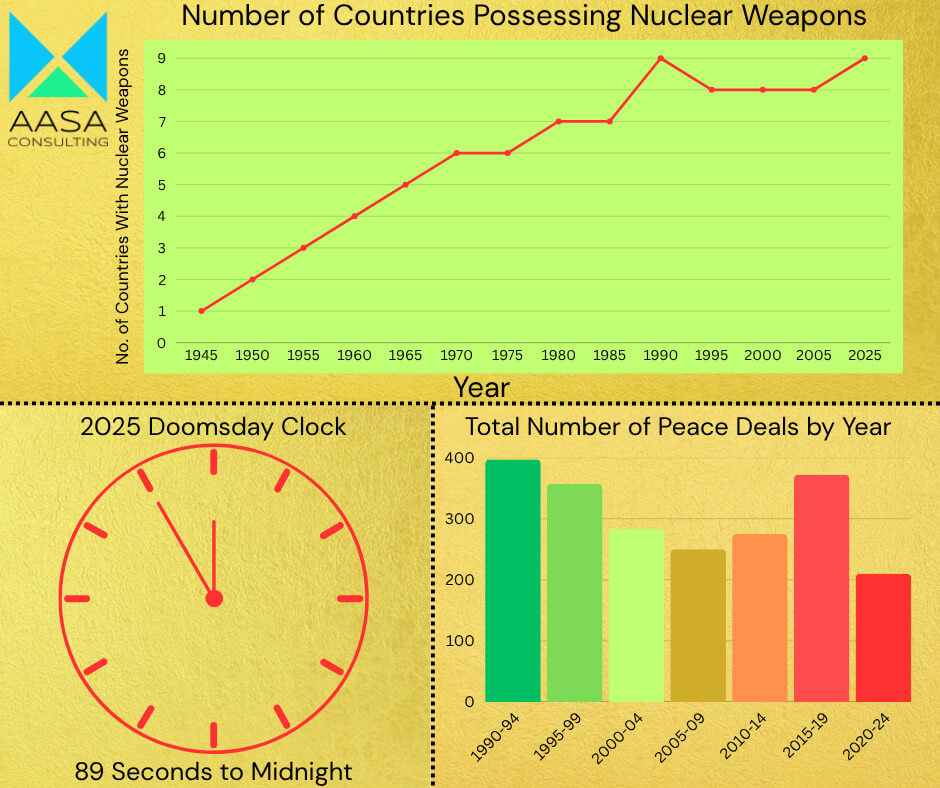

One, very simple and obvious, is the nuclear weapon deterrent. The second reason is that despite the fragility and vulnerability of some parts of Pakistan, such as in KPK or Balochistan, to subversion, there is an inherent will in the people of Pakistan to remain Pakistan.

“There is an inherent will in the people of Pakistan to remain Pakistan.”

Now, there is a lot of disillusionment and loss of confidence among people about the permanence of Pakistan. But I say this because I interact with people at multiple levels throughout the country as part of my voluntary work. In all four provinces, I find there is something called a Pakistani identity that has evolved over the last 78 years, and India recognises this. I don’t see it going to the extreme of full-scale war. There will be tension, there will be conflict but both sides know up to which step on the ladder of conflict they can afford to go, and when they should stop.

Q6. You were a part of the Neemrana Dialogue. What conversations or outcomes have you witnessed, and how do you understand the Indian attitude toward Pakistan?

The Neemrana Group was a non–media-reported dialogue that continued for over 22 years until it was sabotaged by the current BJP government. In terms of how the Indians participated, we should acknowledge that they were willing and interested in learning about Pakistan, and reciprocally, we also learnt. But on balance, we found the Indians far less informed about the realities of Pakistan.

They were keenly interested in Pakistan and wanted to remain engaged. Every six months or so, we would meet and the process eventually contributed to what became the four-point formula during General Musharraf’s time. We would brief our government after every round. At some points, important messages that the Indians did not want to convey through diplomatic channels were conveyed through us. Track II has the advantage of being unofficial, but still endorsed by both governments, who issued visas, facilitated travel, and arranged briefings.

This process helped generate ideas that became practical. For example: facilitating travel across the Line of Control. Since neither side wanted to issue passports, Pakistan not wanting to recognise Indian occupation of Kashmir, and India not wanting to recognise Azad Kashmir, we proposed a single sheet of paper without the stamp of either government. That opened up travel across the LOC. Similarly, bus exchanges started between the two parts of Kashmir. Trade also began for a few years. And the four points reached a stage where the Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was scheduled to visit Islamabad in April 2007 to sign the agreement with General Musharraf.

But Musharraf derailed it inadvertently by dismissing the Chief Justice of Pakistan and the Indian Prime Minister had to cancel his visit. The four points remained unpublicised and unacknowledged.

Q7. Since the Neemrana dialogue has been paused for about a decade, and you likely formed connections with officials and participants on the Indian side, do you feel there is a push from their side to continue the dialogue?

Absolutely, some members of the Indian team have been very disappointed that the dialogue has not continued. And there are others who were not in the dialogue. For example, a gentleman who was not part of Neemrana but who has always been a peace activist, Mr. O. P. Shah, is once again hosting an online conference about Pakistan–India relations, the way forward. We did the same thing about three months ago. There are several Indians who want to conduct dialogue but are prevented from doing it by the present government’s refusal to enter into dialogue.

Q8. What do you think the state of our relationships with the U.S. and China will be in the coming years?

The challenges in our relationship with the United States are far more complex than our relationship with China. With the United States, it is somewhat bizarre that a country 10,000 miles away from us exerts such a disproportionate influence on Pakistan. It has done so partly because it is the single largest export market for our textiles. On the other hand, most of our imports come from China. We have a very unusual relationship: for exports we are so dependent on the U.S.; for imports we are so dependent on China.

“It is somewhat bizarre that a country 10,000 miles away from us exerts such a disproportionate influence on Pakistan.”

The relationship with China is more mutually respectful than it has been with America. We were the second Muslim country after Indonesia to recognise China and the first country to establish an international airline connection for China, In 1971, Pakistan was the key pivotal country that facilitated top-secret contact between China and the United States. Henry Kissinger, as the envoy of President Nixon, flew into Rawalpindi. He then took a night flight from Rawalpindi to Beijing and met Chairman Mao Zedong and Prime Minister Zhou Enlai for the first time, agreeing to make China a permanent member of the UN Security Council in place of Taiwan.

China has been a very special and consistent ally of Pakistan, unlike the U.S. Yet Pakistan’s location and possession of nuclear weapons, and the fact of being Pakistan, are extremely relevant to the United States from its own geostrategic point of view. Therefore, each relationship has to be dealt with on two levels: one on a purely bilateral basis of mutual interest and mutual respect, and the other in the larger regional and global context of their realities.

The United States has 800 military bases around the world. That capacity to intervene anywhere on short notice makes it important for us to maintain a relationship with the U.S. As an economic power, as a cyber power, China’s growth is phenomenal. In peaceful uses of nuclear energy, it has helped energise Chashma, it has supported armament production, and it has launched CPEC. Ironically, China is such a reliable friend, yet we know so little about China. In the next 10 to 20 years, hopefully we will correct this imbalance, appreciate how much we need to learn from contemporary China and absorb and apply some of those models to Pakistan.

Q9. People are becoming disillusioned with Pakistan, but you remain optimistic and argue that Jinnah's vision was not unsuccessful. As people become disillusioned, what are your arguments for maintaining optimism?

You know, disillusionment with a nation-state that you happen to be part of is a common phenomenon, even in countries that are supposed to be far more developed than us. For example, look at the UK, where similar discontent and desire for separation have arisen in Scotland, Wales and Ireland, with part of Ireland having broken away already. French-speaking Canada, about 25 or 30 years ago, wanted to leave English-speaking Canada.

“It will take time for citizens of nation-states to remain abidingly confident about where they live.”

Partly this is because the concept of a nation-state, where the state is citizen-centric instead of ruler-centric, is a relatively young concept in world history, only about 300 to 400 years old. It will take time for citizens of nation-states to remain abidingly confident about where they live.

And some of us like to compare ourselves to India, but whether it be stark poverty or other issues, India also has immense problems. These doubts exist in Pakistan, yes, but we must work to reduce this loss of self-confidence, when we have so much else to be confident about.

Q10. You are a filmmaker and have been involved in media throughout your career. What role do you think media plays in peace and diplomacy between countries, and what kind of content can we produce to encourage positive relationships with our neighbours?

Media shape public opinion through the narratives they present across entertainment, news, and other forms, yet the public can also resist this influence and form independent judgments. My experience with the South Asian Media Association, which brought together editors and media proprietors from across the region, showed both the potential and limits of media cooperation. We drafted a media charter urging restraint and rejecting the use of media to promote inter-state hatred, and it was endorsed by SAARC leaders.

Yet political shifts have undermined these efforts. Hindutva-driven politics in India has effectively nullified the charter, and the once-active forums for dialogue between Indian and Pakistani media leaders no longer exist. Propagandistic films and hostile coverage have replaced balanced exchange. However, similar trends once appeared in Bangladesh. But once she was removed from office, people began to reassert their good for Pakistan and Pakistanis. So, while media can spread virulence, people have the capacity to withstand propaganda and believe in some value system.

“While media can spread virulence, people have the capacity to withstand propaganda and believe in some value system.”

I am not 100% certain that this will always happen. Virulence can have an abiding impact, and all of us have an ethical and moral responsibility to use media with great respect and restraint.

Q11. Do you think social media or new media forms could be a big part of spreading truthful information? For example, in the case of Palestine, TikTok and Instagram helped bypass traditional media silence.

Absolutely. Social media has changed the whole concept of who owns media. Conventional media is owned by a few people, whereas social media belongs to everyone. One single individual can generate content and share it worldwide through YouTube or other platforms, which has never happened in human history before.

Now, with the new menace of artificial intelligence and the fabrication of videos and audio, it is going to become even more challenging. How do you use social media and ensure that truthful, accurate, fact-checked content goes out? With AI, we have invented for the first time in human history a tool whose consequences we ourselves are not able to predict. We knew, when humanity invented nuclear weapons, what they could do: destroy 200,000 lives in minutes. But with AI, we do not know how it is going to supersede the human mind. Then you apply that to discourse between countries where there are already pockets of hate and they magnify that. For example, three years ago, the European Union conclusively proved that India was systematically facilitating and funding disinformation units located outside India to use social media to malign Pakistan.

We have this challenge to meet in both social media and conventional media, but it still can be used to bring about greater understanding and respect between neighbours and people at large.

Q12. How do you think we can find peace at home in Pakistan, given the polarisation in our society? Do you have a way forward or a recipe for restoring peace?

Even with the engineered, partly false democracy that we are presently witnessing, our people have demonstrated extraordinary maturity and rejection of propaganda against a particular party. The independent candidates, with a huge variety of election symbols, managed to get more votes than parties with known symbols. We can only go forward when there is respect by the institutions in our country for the actual will of the people. In a multi-party system, there is inevitably going to be discord and conflict. That is the whole basis for the Western notion of democracy: you must have an opposition. If we have chosen to live with a multi-party system, we will have to learn how to temper the partisanship of multi-party democracy.

“We can only go forward when there is respect by the institutions in our country for the actual will of the people.”

Polarisation, political and economic, will continue. Inequality exists elsewhere, but in our country inequalities can be very sharp and painful. It is estimated that about 30 to 40% of the people live below the poverty line. We need long-term viable solutions to reduce poverty levels. The challenge is how our institutions and our public discourse system, our civil society, manage polarisation so it does not become violent.

However, even though extremism exists, the people of Pakistan are not extremists. In eleven general elections held since 1970, the people of Pakistan have never elected an extremist religious party to public office. They have always elected moderate, middle-of-the-road, balanced political parties. This is a great sign, and the state and society should recognise the strengths and virtues of the people of Pakistan. Institutions should function within their respective domains, and the military should not take over what the civil political responsibility should be. Equally, the civil and political spheres should not just cave in and allow other institutions to take over their role. They should become more competent, confident, and assertive of their rights.

One hopes that this generation and generations will make that possible. I have faith and I have hope that eventually this will happen.

Thank you for your time and valuable insights.

Thank you, it was a pleasure.

Click to share

Recent Blogs

November 11, 2025

November 3, 2025